The Brilliance of Erik Spoelstra Has Allowed the Miami Heat to Conquer Offensive Spacing

I love the old coaching paradigm: Spacing is offense, and offense is spacing.

It sounds so simple and downright obvious, especially when most who have played or watched basketball know the importance of the three-point shot these days. As evident as it may be, so much nuance goes into actually creating that space.

Most adults or teenagers with some playing experience at the middle or high-school levels may recall something nearly every coach runs: some form of a 3-on-2 transition drill. The instructions from the sidelines almost never change: “Score quickly, you have an advantage!” or “Get a layup or wide-open shot in three passes or fewer!” Sometimes, though, the audible groans of a coach fall upon deaf ears, and even at the highest of levels we see mistakes. Turnovers. Sloppy passes. Poor decisions.

If you’ve ever played—bear with me if you haven’t—you know how important spacing is during those advantaged attacks. Both defenders are instructed to start in the lane so they shrink the floor and protect the basket. One will take the ball; the other will split between the rim and the remaining two runners. If all three offensive players gravitate toward the rim, the drill becomes easy for the defense; they don’t have to move very far when the ball gets passed. But when the offense stays wide, stops at the three-point line and makes adept decisions and passes, good luck to any defender hoping to force a contested shot. Once one of them chooses an offensive player to check, the man with the ball leverages the player left open. Everything from there is clockwork.

The same concepts ring truer in 5-on-5 basketball, where more bodies are added to the equation. Spacing not only helps the offense get to the rim for an easier shot, but it compels a defense to commit in a certain direction, opening up teammates away from the ball.

With time, space and simple reads, average players progress to become above-average players. Good players can evolve into great ones when they master that skill and manipulate the defense. Great players become elite when they combine efficiency and volume while also staying a step ahead of defenses that morph to combat their strengths. All this thanks to fantastic spacing.

Perhaps that’s why the Miami Heat were so wildly successful in the second-half of 2016-17. D-League call-ups became rotation regulars, and effective ones at that. Dion Waiters was unleashed with greater efficiency and value. Goran Dragic posted All-Star numbers, averaging 21.4 points and 5.3 assists with a 41.1 percent three-point clip once Miami flipped its fortunes.

It’s not 2013 anymore. Head coach Erik Spoelstra does not have three of the most elite basketball players on the planet at his disposal. But he does have a system, both a tactical approach and teaching methodology, that simplifies a sophisticated game. That structure and tutelage allows the Heat to compete with any given team, on any given night, no matter what their active 12-man roster looks like.

The Initial Innovation

In the summer of 2011, Spoelstra had nearly six months between an NBA Finals loss and the Heat’s first game following an embattled lockout. As the story written by ESPN.com’s Tom Haberstroh goes, he became a student again, seeking out one of the best offensive minds across all sports: then-Oregon football coach Chip Kelly. Spoelstra went to Eugene, Oregon to learn directly from Kelly, envisioning an offense where ease was imparted upon his star-stuffed roster and the benefits of its individual skill could be utilized without constraint.

What Spoelstra gained from Kelly and the trip to the Pacific Northwest stretched deeper than just game tactics, trickling down to the minutiae of how to run the most effective practice. Moving quickly, deliberately and efficiently during these in a “No-Huddle” manner keeps the attention span of athletes, maximizes the reps each player gets and, in turn, ensures more teaching points are relayed and absorbed. Spoelstra is a master at communication, only speaking with players for as long as it takes to deliver the intended message.

The most important nugget Haberstroh uncovered is the tipping point behind Spoelstra’s offensive innovation—a driving force that ultimately served as the initial pivot into a different brand of basketball altogether.

“Everything needed to be fast, instinctual and responsibly impulsive,” he wrote. “That includes forgoing play calls every time down the court. Spoelstra realized that the Heat’s playing style and roster didn’t need to be confined by convention.”

There it was. Positions, and their constraints, were demolished, and the game—as well as the court—opened up as a result. Spoelstra would no longer walk through a new play and explain that “the 4-man does this” and “the 3-man cuts here.” Instead, his directives were based on personnel. Everyone needed to know every spot.

How do coaches implement that stark of a shift? Simply change what they ask from their players. By utilizing more places on the floor and counting on big men to knock down shots away from the hoop, the lane became a vacant place for guards and wings alike to thrive in a drive-and-kick game.

And so, the Heat won two titles with Chris Bosh at center, sucking all the life out of traditional bigs like Kendrick Perkins for the Oklahoma City Thunder, Roy Hibbert for the Indiana Pacers and Tiago Splitter for the San Antonio Spurs. Public perception started to shift. “Monsters” became known as “trees.” Shooting was infinitely more important than back-to-the-basket scoring. Positional versatility became en vogue.

Spoelstra certainly isn’t the first or only coach to think of these strategies within the game of basketball. Mike D’Antoni revolutionized speed and space play almost a decade earlier, and many others began to drift towards that path before the 2011 lockout. But nobody won as much or as immediately.

Fast forward to last season. Miami started the year 11-30, racking up only four victories in the month of December. A 13-game winning streak saved its year and vaulted them back into playoff contention. Changes were certainly made internally, but mostly, the roster finally began buying into Spoelstra’s revamped offense—this time built around its true and elite big man, Hassan Whiteside.

The irony shouldn’t be lost here. Spoelstra first figured out how to win without a pure post player. Now, as the rest of the league has followed suit, he’s trying to buck the trend he created and win around a more traditional tower.

Dissecting Miami’s offense almost feels like a disservice when the team posted a top-five defensive rating despite its uninspiring depth chart and abysmal start. But it’s easy to identify Whiteside as the key to vaulting the defense towards the top. The offense…well that’s more of where Spoelstra’s innovations take hold. Hopefully he can gain enough recognition for more casual fans to finally elevate him into the top tier of all-time sideline greats.

Spo’s Genius in Action

Let’s make one important distinction as we dive into the film: Spacing is about the actions of the four players away from the ball. They can stand, they can cut, they can screen. Any of those factors will create room for the ball-handler. No matter where the rock is possessed, quality spacing is essential. Get the ball in the middle of the court with the intent of opening windows for basket attacks and kick-outs, and all four teammates must be standing in the right spots to keep those windows open.

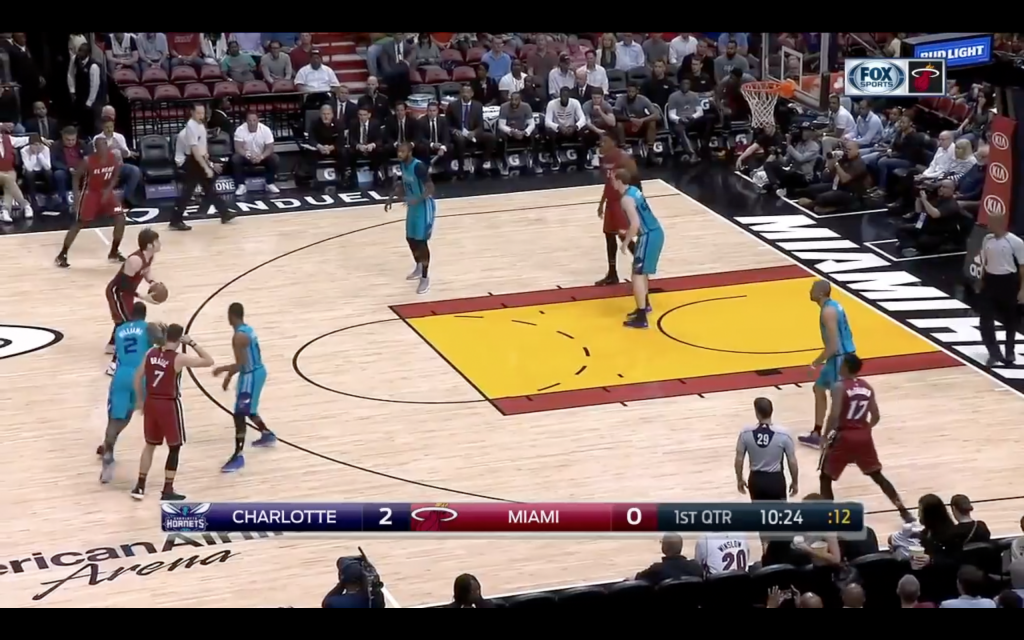

When the ball is not centered, a strong side (where the ball is) and a weak side (the opposite end of the offensive half) emerge. Spacing doesn’t just exist in the gap between the two, but between the players on each end. A total read-and-react early-offense play that’s likely not a called set is the perfect illustration of what happens when all these principles collide:

It’s elementary, my dear Watson.

A side ball screen, set by the monstrous Whiteside, is meant to give him an easy roll to the rim or a centered drive. As the possession gets driven towards the middle, the spacing on that weak side is immaculate. One shooter in dead corner, another on the wing about eight to 10 feet away and a third on that same side of the floor, but trailing the play enough so the ball can quickly swing to him.

The rock eventually finds its way to the trailing Dragic, with Luke Babbitt running into an impromptu high ball screen. The Heat can play this way, unscripted, because no player has his toes stepped on or must move to accommodate on-a-whim decisions. Babbitt and Dragic catch the Charlotte Hornets ill-prepared to disarm the screen, and the former put downs a triple.

Should Babbitt choose to put the ball on the floor, those driving lanes are still clear. The spacing is perfect, and the paint is more open than a 7-Eleven:

So many teams at all levels utilize the three-point arc for offensive decongestion, but not nearly enough use it right.

Standing on the line—or “toeing the line,” as I’ve been taught—has two distinct downsides. First, it provides smaller windows of space than standing a few feet behind the rainbow, as the defender is that much closer to protecting the lane. Second, shooters who start behind the arc can move in on the catch, get momentum to carry them towards the basket and still generate three points for their efforts. Toeing the line makes the shooter choose: lose momentum and fire from a standstill position, or take that step towards the hoop and try for two points instead.

Notice the snipers on the wings for the Heat? They’re all standing far enough behind the three-point marker to accomplish both tasks. Almost all of Spoelstra’s set plays include this detail, but the fact Miami’s free-flowing, improvisational offense results in the same spacing is even more impressive—no doubt the byproduct of meticulous practice and an unwillingness to accept anything less than (near-)perfection.

Speaking of those sets that Spoelstra designs, many of them are common actions opened up by slashers reaching the corners and other appropriate spots. Screens and cuts don’t need to be set strictly in scoring areas. In fact, the more a team can push the boundaries on how far away from the basket a defense will legitimately guard an action, the more area and time the guy near the ball-handler has to make the right read. That sometimes means the ball-handler even backs up and initiates the offense while standing on the half-court logo:

Getting this much room off a pick that takes Dragic to the sideline doesn’t happen if the ball is located directly at the top of the key. And as outlandish as it sounds, Minnesota Timberwolves defenders Andrew Wiggins and Tyus Jones need to play legitimate defense on the feigned guard-to-guard screen Dragic appears to set. Is Waiters a threat to score from there? Probably not. But the Wolves know that if they don’t guard it honestly they have a wide-open and unprotecte lane behind them.

We’ve seen how pick-and-pop big men thrive amid this floor balance, and how scorers and ball-handlers can make easy reads as a result. What about Whiteside? The poor-shooting, even-worse-passing interior player has such a limited arsenal. Perhaps no center benefits more from the offensive structure around them than him:

To be sure: This marks a defensive lapse, but the error is only so egregious due to Miami’s work away from the ball. Open space allows a slipped screen, which Whiteside does here, to net a few points every game. Myles Turner jumps the impending pick too soon, and the help defenders don’t have time to cover the distance separating them from Miami’s rolling big man.

Not one of these three plays bends the brain or is a brilliant action no one else has drawn up before. The game is kept simple in South Beach, spreading the floor for pick-and-rolls, extra passes and rim attacks. But within that simplicity lies complexity—nuance that manifests itself in the exactness with which Spoelstra convinces his players to champion this style.

Sometimes, the best innovators aren’t the ones who reinvent the wheel.

They’re the ones who spin it more precisely.

Spacing: The Next Frontier

How far can the Heat take their stylistic tendencies? Look to Sioux Falls and their G-League affiliate: the Skyforce.

Head coach Nevada Smith—a former Division III coach plucked out of obscurity by the Houston Rockets for his fast-paced, shooting-and-analytics approach—is pushing the limits for what their offense can do. Smith is the perfect lab experiment for franchises wondering how they might be able to innovate and create more space, more speed and more points on the offensive end.

While I’m constantly skeptical of any spacing ratings, metrics or advanced statistics out there to encapsulate the true value of off-ball movements, there’s no denying all these gadgets uniformly point to the Heat being among the league’s best in this regard. Simpler stratagems, like Mike D’Antoni’s, create extra room by launching so many threes. In essence, they bait their opponents away from the basket by credibly taking and making lower-percentage outside bombs. But Spoelstra, unlike the other coaches from teams atop these spacing ratings, is able to accomplish this without succumbing to a green-light approach. Miami continues to hover around league average in three-point attempts per game.

Spoelstra’s attention to detail and belief that every word and nicety he obsesses over makes a difference is what separates him from the pack. He is a perfectionist at heart, and understanding his coaching style and personality is the key to figuring out how the Heat succeeded as much as they did last season. And they will continue to innovate and tinker so long as he’s on the sidelines, zipping through practices and nurturing a culture founded upon hard work and efficiency.

Winning 41 games and missing the playoffs will irk Spoelstra, who is undoubtedly listening to some leadership podcast or studying his craft while you read this. It will bother him so much that the Heat, despite a nearly identical roster, will look different next season, both stylistically and functionally. Miami will have a new way to utilize spacing and its other strengths, this time with an improved mentality and unity that’ll be forged in October instead of January.

Don’t be surprised when Spoelstra exceeds expectations yet again and leaves everyone asking what’s become an annual question: How the hell did he do that?

Follow Adam on Twitter @Spinella14.

Follow NBA Math on Twitter @NBA_Math and on Facebook.

Unless otherwise indicated, all stats are from NBA Math, Basketball Reference or NBA.com.