Inside Out: Welcome to the NBA’s Booming Era of Positionless Offense

Standing next to Nik Stauskas for the first time was an awe-inspiring occasion. “Damn, this guy is huge,” I thought to myself. “He looks so much smaller on television, and he’s a guy that never strays inside the three point line.”

Casual fans often forget just how big routine perimeter players are. Size is abundant in today’s NBA, regardless of role on the court. Stauskas is and always has been a sharpshooter, but other guards who are only 6’6″ likely played interior roles more frequently on their high school, AAU or even collegiate teams. What do you do with a player who is so used to dominating in the post, then gets to the NBA a few years later and is one of the smaller players on the court?

Innovations to how the game has been taught over the past few decades are catching up to that notion and breeding a style of play where everybody boasts skill away from the basket. Big men can shoot! Dirk Nowitzki, Rasheed Wallace and others popularized the movement. If big guys can do more than just score in the post, they can become so much better!

Beyond that, they make their teammates better. While NBA and analytic circles search aimlessly for a way to properly quantify how much the added spacing of one fewer back-to-the-basket player really contributes, there is one tangible effect: Guards who thrive in a back-to-the-basket role now have more space and opportunity to do so.

In essence, offenses are becoming inside-out when compared to traditional notions of how the game should be played from just a few decades ago.

This past season there were 39 players listed at 6’10” or taller who shot more than 82 three-pointers (at least one per game across a full season). Of those 39, all but four shot above 30 percent. The league average was a shade over 35 percent this past year; half the 39 on this list were at or above the 35 percent mark, proving that the necessity for volume is no longer done for volume’s sake—these are good shots that are going in at the league-average rates.

The versatility within that group of bigs is more basic than just their ability to shoot from the perimeter with their size. Six guys (Giannis Antetokounmpo, Nikola Jokic, Marc Gasol, Al Horford, DeMarcus Cousins and Blake Griffin) tallied more than 300 total assists on the season. Another group of six (Karl-Anthony Towns, Kevin Love, Anthony Davis, Joel Embiid, Cousins and Jokic) averaged at least two offensive boards a game. Four averaged at least two blocks, and two shot better than 60 percent from two-point range. There’s a ton of unique two-way play that can distinguish one player’s role from another.

Best of all: This revolution of the game is still in its infancy. Of those noted 39 players, only five are above the age of 30. Just as many on the list were in their rookie season. We can probably thank the AAU game for its contributions here, encouraging star players to bombs away from three, since the ball rarely gets slowed down enough to enter setup shop in the post. Regardless, the mounting versatility within the game creates a plethora of new actions, spacing and general offensive innovation.

It just so happens the smartest teams in today’s NBA landscape are taking full advantage of these changes, often leaning on positionless basketball and the doors this approach opens on the offensive end.

Golden State Warriors

What would be the point of having a 6’9″ point guard and not playing him in the post?

As a member of the Golden State Warriors, the title of “point guard” is irrelevant to Shaun Livingston; his role in the second unit is anything but. He is one of the best and most well-known post threats in the league, and based on the size of the lineups Golden State trots onto the floor, Livingston is frequently guarded by a smaller foe who cannot combat his back-to-basket skill.

Steve Kerr and several of Livingston’s past coaches have put him into the post when he’s able to go one-on-one with a puny defender, and his stats from this past year are impressive out of those situations. Fifteen percent of his possessions came from the post, with a turnover rate of only five; just a season ago he was in the 87th percentile of post-up scoring, averaging an incredible 1.0 points per touch.

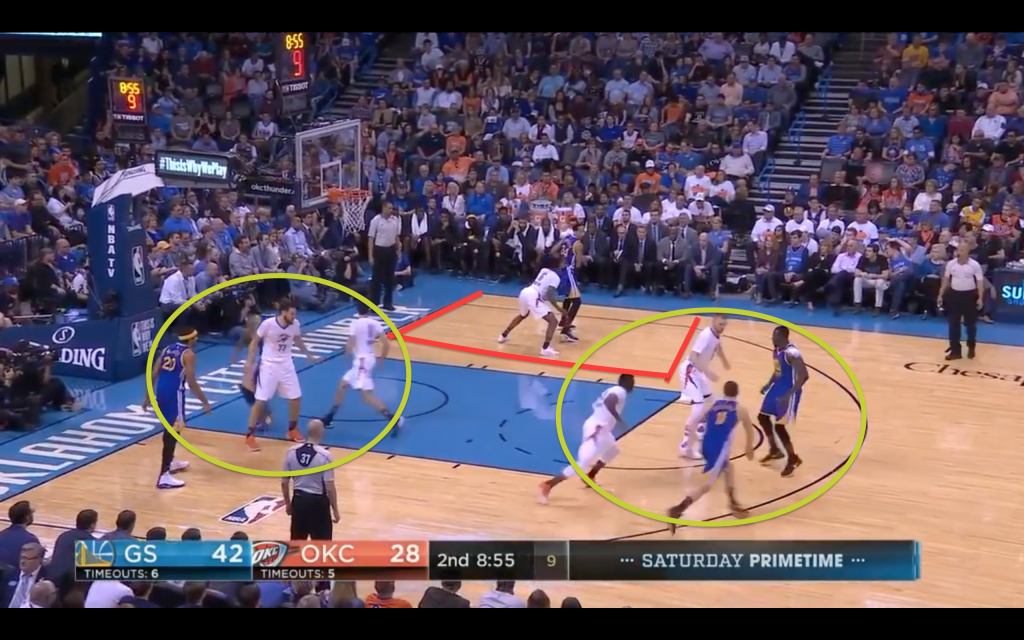

The Warriors need to manufacture enough space for Livingston to operate that close to the basket so he can leverage this skill, and they usually do it while he plays with the second-stringers and at least one true post player. Check out the possession below, where they do so while non-shooter Andre Iguodala is on the court:

Kerr has implemented something called a split cut, where two teammates converge away from the ball and split directions, with one going toward the rim and one to the three-point line. This is always cued by the ball entering the post. The player in the post then has the option to score or use the cut as a weapon against the defense to find an open teammate. Livingston operates on the right offensive side of the floor here, and the Warriors clear out that entire side for him.

Draymond Green and Klay Thompson, two of the most dangerous face-up threats in the league, engage in the split action. Thompson is one of the NBA’s deadliest shooters, and his defender is attached to his hip from the moment the ball crosses half-court.

Green is really the key to the play, though. While his defender, Domantas Sabonis, stands at the elbow to try helping Semaj Christon down low, Green stretches the floor to the top of the key. His three-point range (over 30 percent from deep with more than three attempts per game) and shot chart indicate the top-of-the-key three is a great shot for him. Sabonis cannot drift too far away from him before the split action occurs and emergency double-team Livingston in the post.

The Oklahoma City Thunder scout well and know this Green and Thompson action at the elbow is approaching. Sabonis returns to Green so that he can help out a possible angled screen that gets Thompson open on the ball-side wing. Sagging too far off Green would allow him to nail Klay’s defender and find an elite shooter open from three. Thus, Sabonis returns to Green and stays close:

Look at all the space Livingston has to operate. Essentially, two areas are created on the court. One is the two-man action above, taking place with a pair of dangerous shooters, playmakers and guys who suck defenders toward them with gravity-like force. The second is the opposite side of the lane, where Iguodala and James Michael McAdoo take up space and help Livingston use the lane as a spacing technique. Defensive three-second rules prevent Iguodala’s man from sitting in the lane, and if he makes the decision to abandon Iguodala and trap on the ball, Livingston has an easy skip pass to Iguodala for an uncontested shot.

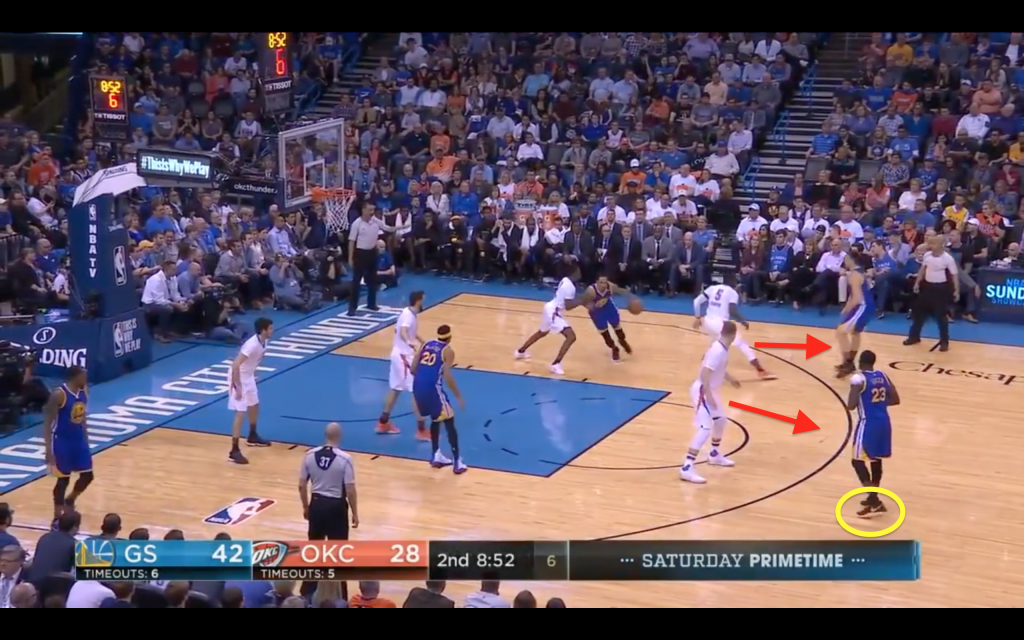

Oklahoma City actually does a fantastic job defending the Green-Thompson action, getting Victor Oladipo through and pestering Thompson by denying him the ball. That spacing a shooter like Green creates comes back into play. Most split cuts end with one player darting for the rim, but since the Warriors want to isolate Livingston, they choose to keep Green high. Oladipo can offer no help in the post off a shooter like Thompson, but what’s to stop Sabonis from double-teaming? Green’s shooting prowess.

By having a stretch big man at the top of the key, Livingston is able to get his jumper off close to the elbow without worrying about a double-team coming. Imagine if Green was only able to space the floor to 18 feet and the half-circle above the free-throw line. Livingston wouldn’t be able to dribble back toward the middle and get this high-quality look.

Boston Celtics

Take a look at the two players listed beneath with their post-up statistics:

- Player A: 0.99 points per possession, 11% frequency, 59.6 eFG%, 80th percentile in output

- Player B: 0.99 points per possession, 9.6% frequency, 52.7 eFG%, 81st percentile in output

Can you tell me who each player is?

Player A is Kelly Olynyk, who has now joined forces with the Miami Heat. Player B is Marcus Smart. That’s right: The Boston Celtics’ backup point guard and stretch-shooting center both thrive in the post when Brad Stevens puts them there. And Stevens, a vocal advocate for positionless basketball, has a bevy of post-up sets and actions dedicated just to Marcus Smart. Watch them, and you’ll notice prime spacing at every turn.

A lot of that spacing can be traced back to either Olynyk or Horford. We saw the effect timing and movement away from the ball can give a player who isolates on one side of the floor. Boston takes a different, and frankly more impressive, approach with their bigs. Playing two towers who are skilled on the perimeter, with two shooters in the corners, opens up a post-up right in the paint for a bully guard like Smart:

The Celtics run a lot of sets with their bigs at the elbows and top of the key and have drafted and developed players who can be shooters and playmakers in these spots. Their most common features a flex action, where Smart serves as a screener on the baseline, then darts off a down screen from one of their bigs. But because both Olynyk and Horford, sharing the floor on this occasion, are such renowned shooters, the Portland Trail Blazers are unable to cheat the action.

Notice where Olynyk’s defender, Al-Farouq Aminu, is when Horford receives the ball. If I’m coaching Portland and Olynyk is not a threat from three, I’m telling Aminu to drop back to the elbow and get one foot in the paint. There he can blow up any cut at the rim and is already in position to prevent a curl on any screen Olynyk would try to set. But his shooting ability makes Aminu get up in his gap from one pass away:

Stick two shooters like Jae Crowder and Isaiah Thomas in the corners, and the result is a great deal of space for Smart to wrestle with his defender in the paint. Even Meyers Leonard has to pressure Horford and respect his passing and shooting ability that far out on the court! There are zero help defenders in the paint as Smart gets ready to receive this entry pass.

Aminu is then slow to rotate down as Smart spins middle, granting him that extra second to get his shot off. No other team uses two shooting big men as well as head coach Brad Stevens and the Celtics, but this play is made possible by the use of Thomas in the back corner. Evan Turner is giving zero help off him, and when the ball goes to Horford, that gives Smart even more space.

Toronto Raptors

Throughout the past few seasons, the Toronto Raptors have rated as one of the NBA’s best offenses. Their lineups have been even better when Patrick Patterson, a versatile defender and above-average three-point shooter who jumped ship to the Oklahoma City Thunder this offseason, takes the floor as their power forward. Patterson provides spacing around the three-point line for a team with two strong, bully guards in Kyle Lowry and DeMar DeRozan. Both are great in the post when they have a size advantage and in ball screens, and head coach Dwane Casey puts them in positions to toggle between these actions and simple down screens while keeping the defense on its toes.

This tends to happen when they run a post-up and provide spacing for DeRozan, who finished in the 96th percentile of back-to-the-basket scoring this past season. DeRozan has proper spacing to score and the ability to come off ball screens when his defender plays him too tight, giving him the edge needed to turn the corner towards the rim:

The post-up is pretty simple.

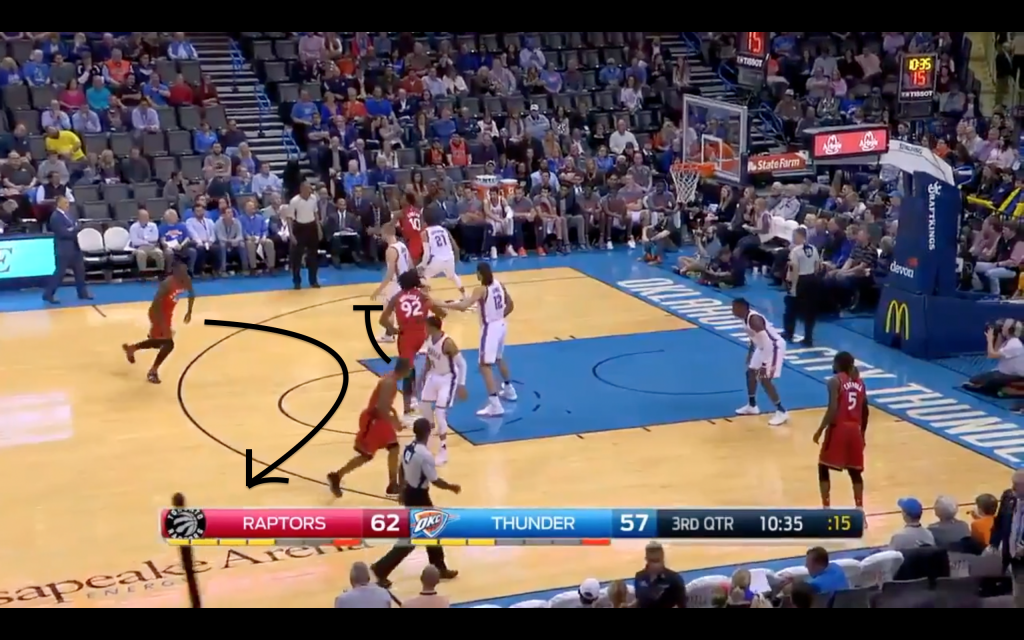

Patterson comes off a back screen from DeRozan, enters the ball to him and then banana cuts to the opposite wing. DeRozan has the entire side of the floor to himself, with three shooters lined up on the three-point line and Jonas Valanciunas on the baseline to occupy help at the rim. It makes DeRozan’s life fairly simple: see help from one player and dish to his man. No movement, no confusion, just a simple kick to Patterson. Mike Muscala over-helps on this play, and Patterson steps into a rhythm three:

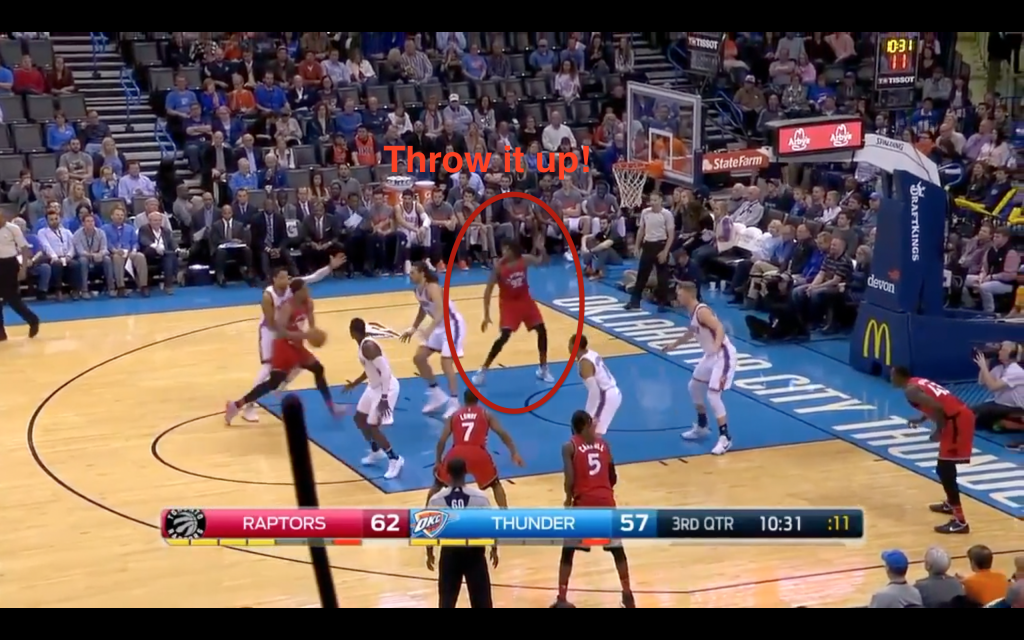

Casey’s offense is exemplary when it comes to counters—set plays that look like a common set but are designed to be different and capitalize on what the defense is anticipating. The second clip in the video above shows the counter for Toronto. Too much attention gets paid to DeRozan, and instead of dropping to the baseline like Valanciunas does, the center cuts through Pascal Siakam’s banana cut and sprints into a ball screen out of the pinch post:

It’s almost impossible to hedge one of these, especially if Lucas “Bebe” Nogueira’s defender is staying low in anticipation of a cut to the baseline. That’s why Nogueira sprints into one of these, and now his defender is trapped. He can stay low and give up an uncontested mid-range jumper to one of the league’s best shooters, or step up and allow the center an unchallenged alley-oop attempt. There’s no good choice here, and as Steven Adams takes one shuffle towards DeRozan, Bebe is ready for the slam:

This entire play is set up by the spacing Siakam provides on his banana cut, and the attention a defender must pay to him when he cuts to the outside.

The first video shows the impact of a stretch 4 perfectly—double-team off him, and he’ll make you pay. But stick too close to him, and the Raptors will run pristine offense in the space he leaves vacant.

(Moral of the story: Toronto is going to really, really miss Patterson, its resident plus-minus superhero.)

Phoenix Suns

The Phoenix Suns placed near the bottom of the league in post-up attempts last season, which was partially driven by their lack of frontcourt players who are above-average scorers in that region. Their most frequent poster was actually young phenom Devin Booker, a multi-talented offensive threat who can shoot, facilitate and operate with his back to the basket. Coach Earl Watson wants to play through Booker, and the organization has made it a point to add stretch-shooting 4s who give that extra spacing on the court.

We take for granted just how open the court is now compared to 20 years ago. Even without an illegal defense call populating the league’s rule book, there has been more room to operate out of the post. It turns out the impetus for this wasn’t penalizing defenses for sagging off their man, but getting bigs who can shoot the ball from the outside. Illegal defense was meant to open up the lane and punish teams for double-teaming in the post. So what do those double-teams look like now?

Booker thwarts this oncoming double-team with a quick move, but the skeleton of the play and movements by defenders highlight the need for spacing in today’s NBA:

Coaches typically seek to double-team the post with the lowest opposite defender—he can double-team or be the help defender when his teammate gets blown by. That would be Blake Griffin here, standing lowest on the court on the opposite side from the ball. As Booker starts his move, Griffin must sprint to help and try meeting him outside the lane.

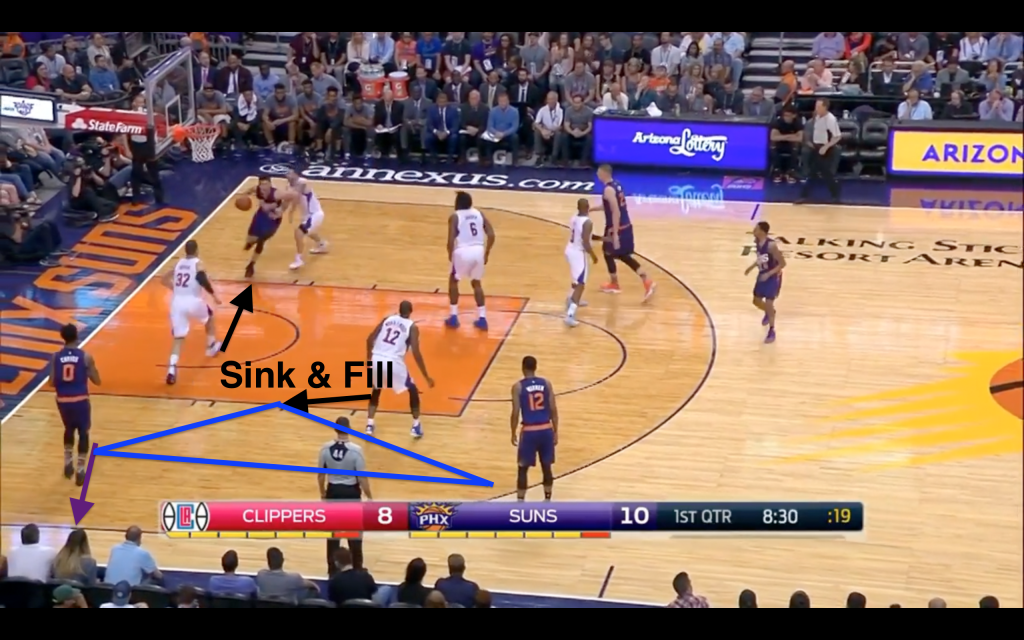

Of course, if Griffin leaves and the rest of the Clippers stand still, his man will be left wide open. The onus is then on Luc Mbah a Moute, standing on the wing above Griffin, to “sink-and-fill”, dropping to split responsibilities between his man and Griffin’s. Here is where the difference between a stretch-shooting big comes in, and why this is the best example to show it.

Marquese Chriss, standing near the baseline, backpedals to the corner immediately after seeing Griffin dart to help at the rim. Why is that so important? Because of the pressure it puts on Mbah a Moute:

Mbah a Moute’s proper position on the court would be standing in the lane, creating a shallow triangle between the two players he has to split on the weak side, slightly favoring towards the rim. The blue triangle designates that split, and the more space between the two players and the ball exists, the more difficult a coverage it is for Mbah a Moute.

Compare the size of that triangle to another Devin Booker post-up, this time against the Utah Jazz, where the Suns do not vacate the block opposite from Booker:

It’s an easier coverage for Gordon Hayward than Luc Richard Mbah a Moute, and not just because the distance he must travel and cover is smaller. In the Jazz’s coverage, Rudy Gobert is able to step towards the ball while also closing the passing window from Booker to Alex Len. Hayward’s job here is to stay on the top side of Len and push him closer to the baseline so he isn’t a threat to score instantly on the catch. Think of what a pass from Booker to his teammate in the corner would look like. There are so many bodies in the way as he drives baseline that Hayward can likely get a hand on a direct pass, while recovering to his man and preventing a shot on a softer, more arched pass.

Mbah a Moute has no such option here, as Booker can directly and efficiently hit Chriss with a pass. If he over-anticipates and tries to gamble on the baseline pass, Booker has a wide-open angle to hit P.J. Tucker for a comfortable catch-and-shoot.

Spacing is offense, and offense is spacing. By giving every player more room in the post, it’s that much simpler to find easy baskets at the rim or uncontested looks from three. This isn’t any ground-breaking revelation, but the usage of stretch-shooting bigs is now manifesting itself in a brand new way: guards who operate out of the post.

Size mismatches can exist anywhere on the court. And by creating this space with unique plays and perimeter skill from the frontcourt, those mismatches are exploited to the offense’s advantage.

Follow Adam on Twitter @Spinella14.

Follow NBA Math on Twitter @NBA_Math and on Facebook.

Unless otherwise indicated, all stats are from NBA Math, Basketball Reference or NBA.com.