The New York Knicks Fired Phil Jackson, But They’re Still Struggling

On June 28th, 2017, ESPN’s Ramona Shelburne reported the New York Knicks and team President Phil Jackson “mutually agreed to part ways.” And for a little more than a week thereafter, it seemed like the Knicks would behave like a rational, calculated-risk-taking franchise.

Then, on July 6th, reports emerged that they were going to sign Tim Hardaway Jr. to a four-year, $71 million offer sheet (including a player option on the final season and a 15 percent trade kicker), despite their presidential role remaining unfilled. It was a confounding decision to say the least, and according to Ian Begley of ESPN, “a move that has been met with shock inside and outside the organization.” Only a few days later, former Cleveland Cavaliers’ general manager David Griffin pulled his name from consideration for New York’s open position, citing differences with the existing executive hierarchy.

For those familiar with the team, this was just another week for a Knicks organization constantly immersed in self-imposed turmoil.

New York handed out the worst contract in the NBA last offseason, paying a declining and injury-plagued Joakim Noah an average of $18 million per year through 2020. So it was surprising to see Steve Mills and Co. hand Hardaway this offer sheet while considering the negative effects of that deal just one year later. This is not to say the situations are the same, but most teams would react to a glaring mistake with a similar contract by becoming a bit more risk-averse. Not the Knicks. ESPN’s Zach Lowe also mentioned the Hawks’ offer for Hardaway was around four years and $48 million, which begs the question of why the Knicks were so desperate to land him.

Most likely because Hardaway wasn’t all that bad for the Hawks.

After a promising rookie campaign in New York, his value and play cratered during his sophomore season. His overall total points added (TPA) in the last three seasons trended as follows, minus-130.96 (1st percentile), minus-36.71 (29th percentile), minus-8.74 (37th percentile). While those are fairly steady improvements, they still leave him in the red. There is room to grow for this 25-year-old, but the Knicks paid a premium to bet on his continued development.

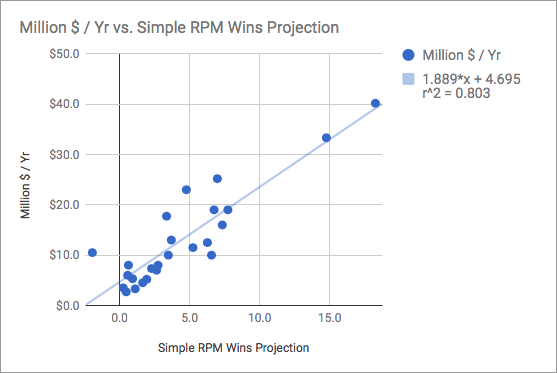

Utilizing Nathan Walker’s (@bbstats) contract value sheet, we see a direct correlation between Simple RPM Wins and an NBA player’s average annual salary. (Editor’s Note: Simple RPM Wins is calculated differently than ESPN’s RPM Wins metric.)

The correlation coefficient (r^2) between these two measures is 0.687, as one can see from the provided graph in the link, indicating a fairly strong correlation between the projected Simple RPM Wins and the average annual salary. When adjusting for just the guard and guard-forward positions—positions most similar to Hardaway—the correlation is even stronger, as r^2 rises to 0.803.

This isn’t the quintessential model, but it helps provide some color by placing a dollar amount on player production through their projected Simple RPM Wins. And considering the results, it is not a great look for the Knicks to provide Hardaway with $7.55 million more annually than his expected contributions.

Nonetheless, the Knicks still had to meet the salary floor. So what else could they have done with the money in his place?

Take a look at the Brooklyn Nets’ decision-making in 2017 alone. Current GM Sean Marks has demonstrated a clear understanding that, after the infamous trade four years ago, there are very few viable means of upgrading the NBA’s most talent-depleted roster. Unlike Sam Hinkie’s Philadelphia 76ers, the Nets’ cupboard (as of a few weeks ago) was essentially bare until 2020.

In February, they traded Bogdan Bogdanovic for the Washington Wizards’ first-round pick and took on Andrew Nicholson’s undesirable contract. They then used that pick and Brook Lopez’s expiring contract to trade for the criminally underrated D’Angelo Russell, but also had to take back Timofey Mozgov’s albatross pact. The Nets then took on DeMarre Carroll’s remaining two years and $30 million in exchange for a future first- and second-round pick from the Toronto Raptors. These are risks, but they’re intelligent ones for a franchise with no direct path forward.

Assuming bad contracts to obtain assets is something Marks, and Sam Hinkie before him, have done extremely well. On the contrary, settling for long-term deals that overpay role players can potentially become problematic.

The Portland Trail Blazers are a perfect example of this. Armed with tons of space after the salary-cap spike in 2016, they whiffed in free agency, handing out several eight-figure, long-term deals to Mo Harkless, Allen Crabbe, Evan Turner and Meyers Leonard. None are necessarily bad players, but committing 57 percent of their 2017 salary to a bunch of role players has hard-capped them and made it nearly impossible to improve the roster (barring a salary dump or landing a star in the draft) through 2020.

The Knicks could have maintained big-picture financial flexibility, giving players of similar quality more average annual value than Hardaway, but for a shorter period of time. This method would have kept the books, for the most part, clear as they look to upgrade the roster when Kristaps Porzingis becomes eligible for a max extension after the 2017-18 season. Instead, they have roughly 35 percent of their cap tied up between Hardaway and Noah for the next three seasons, which will push the needle very little, if at all.

With all that said, Hardaway was a decent player last season. Knicks head honcho Jeff Hornacek ran a good deal of “Horns” sets in his previous stint in Phoenix, and without Phil Jackson attempting to force the triangle offense onto his players and coaching staff, he might revisit these on a more regular basis. And if that’s the case, it will benefit Hardaway, as these actions involve plenty of screens and pick-and-rolls for shooters, like the play below (courtesy of BBALLBREAKDOWN):

And if the ball-handler is able to split the trap on a high PnR, he should create open looks by drawing help from the wings, as shown in the clip below:

Hardaway can create his own offense; he averaged 0.98 points per possession (PPP) on isolations in 2016-17 (78th percentile) and 1.15 PPP on 3.4 spot-up attempts per game (85th percentile). Additionally, he was an above-average finisher in transition, averaging 1.17 PPP (65th percentile)—particularly noteworthy since the Knicks finished in the bottom three of transition PPP for the second-consecutive season last year. Despite the fact that he wasn’t a great motion shooter—Hardaway shot 37.0 percent on pull-up jumpers and 37.5 percent on catch-and-fire possessions—the Hawks offense improved by 8.9 points per 100 possessions with him on the floor to produce a 110.0 offensive rating.

He also saw his shooting percentages improve dramatically on the back end of the season with an increase in playing time.

Furthermore, Hardaway had 56.82 offensive points added (OPA), which put him in the 89th percentile. At 25, there are plenty of signs that his game will continue to improve, though it’s far from a given. He hasn’t yet come close to having a positive impact on the defensive end. His best season came in 2015-16 when he posted minus-20.98 defensive points saved (DPS), placing him in the 27th percentile.

Yes, there is a chance Hardaway lives up to his pricey contract. But the Knicks are going to be a bad team for the foreseeable future and took an unnecessary and potentially crippling risk for the second time in as many years.

It’s these type of decisions, coming even after Jackson has left the organization, that threaten to inhibit long-term progress and hold back a franchise desperately seeking to regain its relevancy.

Follow Tim on Twitter @StubbHub.

Follow NBA Math on Twitter @NBA_Math and on Facebook.

Unless otherwise indicated, all stats are from NBA Math, Basketball Reference or NBA.com.