Ben Simmons is Dominating for the Philadelphia 76ers without a Jumper…But How?

Ball-dominant players who have a track record for being unable to make long-distance shots typically receive heaps of criticism. Players like Marcus Smart, Elfrid Payton, Ricky Rubio and Rajon Rondo each possess an array of beneficial skills, but their shooting woes are firmly ingrained into the NBA discourse.

Non-floor spacing distributors limit a team’s offensive utility. Quality shots become dependent on paint penetration. They allow an opposing guard to freely roam into passing lanes and disrupt the flow. Without a pull-up threat in pick-and-roll sets, defenses can sink back into the paint. If the team doesn’t roster enough ancillary floor-spacing threats, that area becomes overly congested. Running simple motions suddenly becomes pretty complicated.

Enter Ben Simmons.

The unicorn rookie point guard is scoring at an All-Star clip, despite the fact everyone in the arena and watching on television knows about his shooting struggles. He’s led the Philadelphia 76ers to an encouraging 12-9 record, and he currently ranks 13th among all players in NBA Math’s total points added metric. Simmons is averaging a categorically dominant 18.6 points, 7.2 assists and 9.4 rebounds per game on 51 percent shooting.

But we rarely get to see his jump shot. Only 0.8 of his 15.2 field-goal attempts per game are coming from outside 15 feet, per NBA.com. He’s an enigma; you won’t find another top-30 scorer who plays in the backcourt and openly refuses to launch from the perimeter. Most elite point guards are attempting four or more triples per game. Even point forwards like LeBron James and Giannis Antetokounmpo hoist a handful each night, whereas Simmons has attempted only eight three-pointers total, most of which have been buzzer-beater heaves.

His shot is beyond ugly. Some have questioned whether he’s shooting with the correct hand. He even experiments with right-handed free throws before games. For now, though, Simmons is a lefty who grapples with a confidence issue and lacks basic fluidity in his shooting form. And, on top of that, he regularly twists his lower body to find the proper balance, which interferes with his stroke:

Taking Advantage of What the Defense Gives

Since the beginning of basketball, defenders have tended to sag off from non-shooters. But Simmons has become adept at using the afforded shooting space to supplement his world-class driving abilities.

The 21-year-old is second in drives with 19.0 per game, per NBA.com, and identifies attack lanes with ease. When he’s provided a shooting cushion, it invites him to get north-south with a head of steam before having to confront any ball pressure. And once he builds downhill momentum, his oversized 6’11” frame helps shield off defenders and extend the ball away from contesting swat attempts.

Watch here as Thabo Sefolosha sinks back into the paint, essentially daring Simmons to pull up for the jumper. Instead, Philly’s rookie skillfully attacks toward the middle, earning two momentum-building steps before incurring any defensive resistance:

Simmons might as well be escorted to the rim if he has an open runway like this one. The rest of the league is quickly learning that, regardless of how much it tries coercing him into open jumpers, he’s determined to reach the rim on every possession. Sixty-seven percent of his attempts are from within five feet of the basket, per NBA.com.

Big Ben is a physical specimen with a superlative combination: the power to muscle through smaller defenders, and the shiftiness and burst to maneuver past bigger ones. Tack on his innate awareness of when to change direction and speed, and Simmons becomes unstoppable once he takes control of an open driving lane.

Here’s an example of the variety in his arsenal:

His guard-like agility helps him stop on a dime, then shift directions with a crisp behind-the-back dribble. And then he uses his extreme length to shoot the floater over a 6’8” Bojan Bogdanovic.

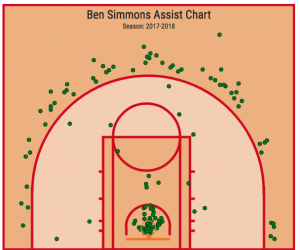

Call him a point guard or a point forward. It doesn’t matter. Simmons’ court vision separates him from the ordinary facilitator either way. Sixers head coach Brett Brown is running the offense through him, and his court vision mushrooms when his on-ball defender backs off. He leads the league in passes made per game (74.7) and is 11th in total assist percentage (33.4).

Simmons is making plays you would only expect from seasoned veterans. While he may not space the floor with his own shot, he similarly creates creases in opposing defenses with precise cross-court passes like the one below:

Simmons showcases his mental acuity on this play. Once the defender cuts him off at the baseline, he gets caught in the air behind the basket. The first read on this set is to find the corner marksman, but Eric Gordon tactfully rotates down to eliminate the passing lane. Like a quarterback, Simmons decodes Gordon’s chess move and transitions to the second read in his progression. He uses the newly voided space to deliver a pinpoint 25-foot laser to Jerryd Bayless for the spot-up jumper. His vine-like wingspan allows him to play above the level of the defense, and he’s a creative mid-air improvisor around the basket.

Working within the System

Non-traditional points guards influence floor spacing, and Simmons benefits from having an abundance of shooting threats around him. The rest of the Sixers’ rotation is stockpiled with willing and capable snipers, all of whom flourish in off-ball roles and let Philly maximize the amount of time he handles the rock.

Bayless, Robert Covington and J.J. Redick all rank in the 70th percentile or better in spot-up efficiency, per Synergy Sports. Having multiple targets on the floor means that defenders cannot help onto Simmons, for fear of losing Philadelphia’s snipers.

The Sixers’ offensive scheme is carefully crafted to emphasize Simmons’ talents. He’s surrounded by shooters and off-ball specialists who provide enough room for him to operate. The Milwaukee Bucks try to maximize Giannis Antetokounmpo in a similar fashion. The difference: Simmons is universally regarded as a true point guard.

While many of his assists occur on drive-and-kick plays, he and Embiid have quickly developed a sophisticated two-man chemistry, and opposing defenses have struggled to handle the mixture of their dynamic talents.

Whether Embiid is trailing the play or working in half-court sets, he’s proved a willing and confident shooter. When put into the roll-man position, he opts to pop out for a jumper 28.9 percent of the time, per Synergy Sports. The balance of pop outs versus rim runs keeps defenses honest, and the big man’s 1.182 points per possessions on pick-and-pop shots ranks in the 77th percentile of efficiency:

Embiid connects on only 26.6 percent of his outside shots, and he attempts just a handful of jumpers per game. But he’s enough of a threat to open up the floor. Rival bigs have to defend Embiid near the perimeter, so Simmons’ defenders are left without any back-end rim protection whenever he drives.

Look at how Andre Drummond slides toward the three-point arc to protect against the pop-out jumper. The basket is left unattended, and by the time Drummond recovers, he has no chance to catch up:

Bryan Colangelo has quietly built a roster chalk full of bigs who capably stretch the floor. Amir Johnson, Richaun Holmes and Dario Saric aren’t knockdown shooters, but each needs to be respected along the three-point line. Pairing Simmons with these types of shooters is a necessity—which, you know, could partially explain why Jahlil Okafor doesn’t play.

But if He Insists on Driving…

All rookies have poor habits that must be broken. And despite Simmons’ polished game, even he has blemishes to clean up.

First and foremost: If Simmons wants to solely make his mark around the basket, then his marginal ambidexterity should be put under the microscope. His blend of left-handed jumpers and right-handed layups and floaters is downright bizarre. And although he may use different hands for separate tasks, the 20-game sample size suggests he’s uncomfortable using his left to finish.

In the following play, Simmons drives into what should be a routine layup for a left-handed player. He has a full step on Dirk Nowitzki and a clear path to turn the corner. And yet, he needlessly corkscrews in mid-air to get the shot off with his right. By doing so, he shifts his momentum back into the recovering Nowitzki, who subsequently helps to force a missed shot:

In this instance, Simmons’ overreliance on the right hand interferes with his vertical alignment, which eliminates any possibility of him squaring his shoulders with the basket. By contorting his body in the air, he increases the odds his shot will be off target.

Here’s another play where Simmons has a straightforward layup but decides to switch shooting hands after taking off. You can tell he doesn’t yet trust the diversity of his finishing moves, and he’ll have to add more variety as he evolves:

Unique length and leaping ability allows Simmons to occasionally get away with some of these circus adjustments, but as the ambidexterity flaw grows more apparent, defenders will take away his right hand. He must stop creating these unnecessary tasks that force the ball to his strong side if he’s to become a clean and decisive finisher. The added motion only gifts opposing defenders more time to recover and contest his shot.

As he matures, he’ll learn to take advantage of split-second defensive lapses in order to convert shots inside of narrow and awkward shooting windows. His overall smoothness will improve once he begins to eliminate the unnecessary action that elongates his layups and floaters at the rim.

With all of this in mind, Simmons shouldn’t be crowned as the unanimous Rookie of the Year quite yet.

Much like the Sixers themselves, this NBA season is young, and Philadelphians don’t need the bad juju. The basketball world was wonderstruck by Joel Embiid for 31 games in 2016, and watching him lose out on the new-kid-on-the-block award due solely to sample size registered as a downcast chapter in the Trust the Process soap opera.

Still: Akin to Embiid last year, Simmons has only needed one-quarter of the season to prove he’s far and away the league’s most talented newcomer.

Follow Matt Chin on Twitter @MattChinNBA.

Follow NBA Math on Twitter @NBA_Math, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

Statistics are accurate as of all games headed into December 1, 2017. All non-cited statistics are from Basketball-Reference.com or NBA.com. All salary information is from RealGM.com.